PortugalExpert - Premium

Navigator

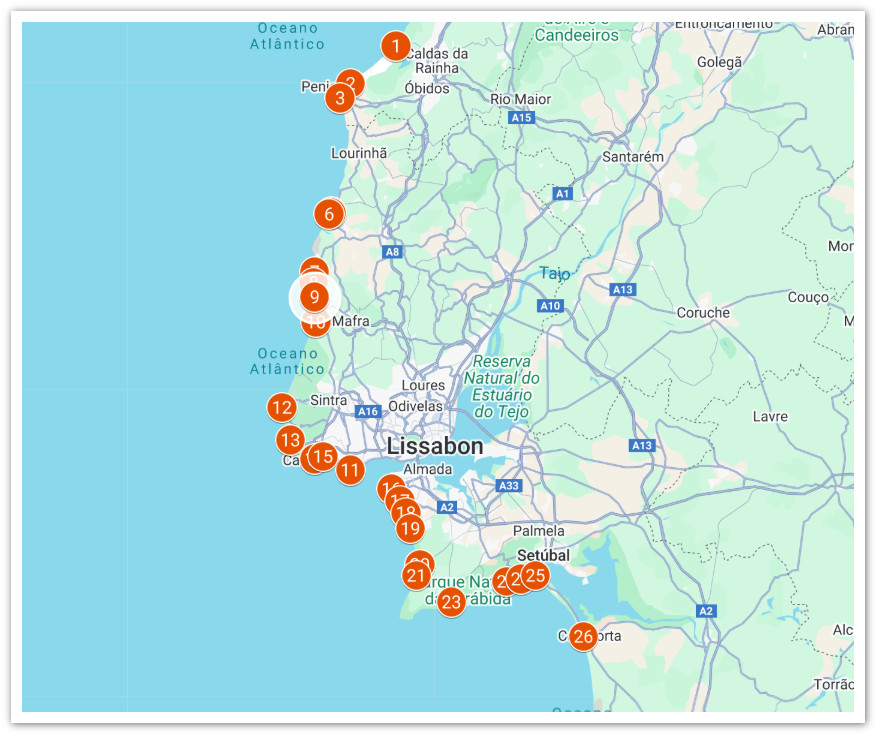

Die besten Straende rund um Lissabon

"Erlebt. Entdeckt. Empfohlen "

Jeder Ort auf dieser Karte wurde persönlich entdeckt und nicht automatisch von KI erstellt – Empfehlungen, auf die du vertrauen kannst."

Klicke einfach auf das Bild, um die interaktive Karte zu öffnen und mühelos den perfekten Strand für deinen nächsten Ausflug zu finden. In der Karte erhältst du zu jedem Strand eine kurze Beschreibung und hilfreiche Infos.

NAVIGATIONSHILFE

Hier findest du eine Navigationshilfe zu allen Straende in der Karte : Klicke einfach auf den Namen eines Strandes – Google Navigation führt dich sicher und bequem direkt zum Ziel.

- Praia da Foz do Arelho

- Praia Baleal

- Supertubos

- Praia da Física

- Praia do Centro

- Praia de Santa Cruz

- Praia da Calada

- Beach São Lourenço

- Ribeira d'Ilhas beach

- Foz do Lizandro

- Ursa Beach

- Praia do Guincho

- Praia da Rainha

- Tamariz Beach

- ONA at the beach

- Carcavelos beach

- Praia da Mata

- Sereia beach

- Fonte da Telha

- Praia da Lagoa de Albufeira (Lagoa)

- Praia do Meco - nudismo

- Praia do Portinho da Arrábida

- Beach California

- Figueirinha beach

- Comporta's Beach

- Praia de Tróia

.

Alfama: The Moorish Time Capsule

I walked into Alfama expecting a neighborhood. What I found was a city that refused to die.

The earthquake hit Lisbon on November 1, 1755. The ground split open. A tsunami followed. Most of the city—the orderly streets, the grand buildings—collapsed into rubble. But Alfama stayed standing. Not because of luck. Because it sits on bedrock. Solid rock that absorbed the shockwaves while everything around it crumbled.

So when you walk through Alfama today, you're walking through the only part of Lisbon that still looks like it did before that catastrophe. Everything else was rebuilt in neat grids. Alfama kept its maze.

The Labyrinth

The streets here don't make sense. They twist, climb, dead-end without warning. Narrow alleys called becos barely fit two people side by side. Staircases appear suddenly, leading up or down without clear destination. I got lost three times before I stopped trying to navigate logically.

There's a local rule: if you want the castle, go up. If you want the river, go down. That's it. That's the entire navigation system.

This chaos isn't random. It's Moorish. The Arabs controlled Lisbon from 711 to 1147, and they built this district the way they built North African cities—winding streets for defense, narrow passages for shade. Even the name comes from Arabic: al-hamma, meaning hot springs. There used to be thermal waters flowing here.

When the Christians reconquered the city, they kicked the Moors out of the castle area. Some moved to the neighboring Mouraria district—literally "Moorish Quarter." But the architecture stayed. The layout stayed. Alfama became a time capsule, not by design, but by survival.

What You See

The houses are painted in faded yellows and whites. Laundry hangs from every balcony—practical, not decorative. Tiles cover some façades, chipped and weathered. The roofs are terracotta, layered across the hillside like scales.

I stood at Miradouro das Portas do Sol at sunrise. From up there, you see it all—the orange rooftops, the Tagus River, the way the streets fold into each other. It looks precarious, like one strong wind could slide the whole neighborhood into the water. But it's been here for centuries.

The cathedral, Sé de Lisboa, sits heavy and fortress-like near the base of the hill. They built it in 1150 on top of the city's main mosque. The symbolism was clear: this is ours now. It looks more like a military stronghold than a church—small windows, thick walls. It was built to last, and it has.

What You Hear

Fado plays from open doorways at night. It's not background music. It's deliberate, mournful, raw. The Portuguese guitar has this metallic resonance that cuts through conversations. The singers don't perform—they mourn, they yearn, they ache. Saudade, they call it. A longing for something you can't name.

Alfama is where Fado was born. Not in concert halls, but in these tight streets, sung by the wives of sailors who might not come back. It's working-class grief turned into art.

Then there's Tram 28. Yellow, screeching, rattling through streets that seem too narrow for it. Locals barely notice. Tourists photograph it compulsively. It's both—a functioning relic.

What You Smell

Grilled sardines. Everywhere. People cook them on small charcoal grills right on the street, especially during summer festivals. The smoke drifts between buildings, mixing with the salt air from the river.

In June, the neighborhood explodes for Saint Anthony's festival. Saint Anthony was born here in 1195. The streets fill with streamers, music, and the smell of grilled fish and wine. It stops being a historic district and becomes a block party that's been going for eight centuries.

What Stayed

Casa dos Bicos stands out—a 16th-century house covered in diamond-shaped stones that look like spikes. It survived the earthquake when everything around it fell. Now it houses the José Saramago Foundation. Walking past it feels like passing a scar that healed wrong but stayed visible.

The Castelo de São Jorge sits at the top. The Moors built it in the 11th century to protect the elite. After 1147, it became a Christian fortress, then a royal palace, then a prison. Now it's a tourist site. But the walls are still Moorish. The view is still strategic. You can see why they chose this hill.

Below, in Campo de Santa Clara, the Feira da Ladra operates every Tuesday and Saturday. "Market of the Thief." It's been running since the 12th century. The name tells you what kind of goods changed hands here.

Why It Matters

Alfama didn't survive because it was important. It survived because it was built on rock. But that accident preserved something deliberate—a way of living that doesn't exist in modern cities. Neighbors still talk across narrow streets. Life happens outside, not behind closed doors. The architecture forces proximity.

I spent two days there and never saw a straight line. Not in the streets, not in the way people moved, not in the rhythm of the neighborhood. Everything curved, adapted, persisted.

When I left, I realized I hadn't taken many photos. I'd been too busy not getting lost. That felt right. Alfama isn't a postcard. It's a place that outlasted disaster by being too stubborn to fall. The Moors are gone. The earthquake is history. But the maze remains, unchanged and unapologetic.

© PortugalExpert 2206

Where Lisbon Begins Again: The Baixa

The difference between Alfama and Baixa is the difference between survival and choice.

Alfama survived the 1755 earthquake by accident—it sat on bedrock. Baixa didn't survive. It was destroyed completely. The entire district, the royal palace, the medieval center—gone. What stands there now was built from scratch, and it was built with intention.

The Grid

When the Marquês de Pombal rebuilt Baixa, he didn't try to recreate what was lost. He imposed order. The world's first grid system for a city this size. Straight boulevards. Right angles. Uniform buildings, mostly three stories, painted yellow and cream. Every street named after the trade that belonged there—Rua da Prata for silversmiths, Rua dos Sapateiros for shoemakers.

Walking through Baixa feels nothing like walking through Alfama. No maze. No surprises. You can see where you're going. The streets are wide enough that sunlight reaches the ground. It's rational, almost severe in its clarity.

This was deliberate. Pombal was an Enlightenment figure. He didn't want charm or nostalgia. He wanted a city that worked, that could withstand the next disaster. They built it with a hidden innovation—the Gaiola Pombalina, a flexible wooden cage built into the stone walls. The buildings could absorb shockwaves. They tested the system by marching troops around prototypes to simulate tremors.

Baixa is what Lisbon decided to become after the worst day in its history.

Praça do Comércio

The royal palace used to stand where Praça do Comércio is now. The earthquake erased it. Instead of rebuilding a palace, they built an open square—massive, U-shaped, facing the Tagus River. The message was clear: this is a commercial capital now, not just a royal one.

I stood at the Cais das Colunas, the marble steps that lead directly into the river. Kings and foreign dignitaries once disembarked here. Now it's tourists and locals sitting on the steps, watching the water. The scale of the square is almost uncomfortable—too much space, too much sky. But that's the point. It declares openness, power, control.

In the center, there's an equestrian statue of King José I, the monarch during the earthquake. He's frozen mid-ride, presiding over the reconstruction he authorized but probably didn't fully understand. The real architect was Pombal, and he's commemorated too, but elsewhere, with less grandeur.

The yellow buildings that frame the square have arcades on the ground floor. They used to house ministries. Now some are restaurants, some are offices. The Arco da Rua Augusta stands at the far end—a triumphal arch that connects the square to the main pedestrian street. You can climb to the top. From there, you see the geometry of Baixa laid out below, every street parallel or perpendicular, and beyond it, the chaotic tangle of Alfama climbing its hill.

Rossio

The Rossio is the pulse. Officially Praça Dom Pedro IV, but no one calls it that. It's been the city's meeting point for centuries—public executions happened here, bullfights, markets, protests.

The ground is covered in wavy black and white mosaic tiles, calçada portuguesa, arranged in a pattern that looks like it's moving when you stare at it too long. It's disorienting in an otherwise orderly district. Maybe that's intentional too—a reminder that not everything can be controlled.

I sat at Café Nicola, an Art Deco holdout on the square's edge, and watched people. Students, office workers, street performers, tourists consulting maps. The Rossio doesn't care who you are. It just keeps moving.

Rua Augusta

Rua Augusta is the main artery, running from Rossio to Praça do Comércio. It's fully pedestrianized now, lined with shops and cafés. Street performers work the crowds—living statues, musicians, people selling trinkets of questionable legality.

Near Rossio, there's a tiny bar called A Ginjinha. It's barely wider than a doorway. Inside, locals and tourists stand shoulder to shoulder drinking ginja—a sweet cherry liqueur served in a shot glass with a soaked cherry at the bottom. You drink it standing. You don't linger. It's a ritual that takes two minutes.

I went twice. The first time I sipped it. The second time I drank it like everyone else—fast, the way it's meant to be consumed. The liqueur is syrupy, almost medicinal. The cherry is soft and tastes like concentrated alcohol. It's not sophisticated. It's just what people do here.

The Elevator

The Elevador de Santa Justa is a cast-iron structure that looks like it belongs in Paris, not Lisbon. It was designed by a student of Eiffel and connects Baixa with the upper neighborhoods of Chiado and Bairro Alto. It's neo-Gothic, industrial, functional.

I took it once. The elevator car itself is cramped and creaky. At the top, there's a viewing platform. From there, you see the grid of Baixa stretching toward the river, and above it, the ruins of the Convento do Carmo. The convent was destroyed in the earthquake and never rebuilt. The roofless Gothic arches still stand, open to the sky. They left it that way on purpose—a monument to what was lost.

The contrast is sharp. Below, everything is orderly and reconstructed. Above, the ruins remind you that reconstruction was necessary because destruction was total.

What It Means

Baixa isn't about memory. It's about decision. After 1755, Lisbon could have rebuilt itself as it was—winding streets, medieval layouts, organic growth. It chose not to. It chose geometry, modernity, control.

That choice is still visible in every street. The buildings are uniform because uniformity was the goal. The grid is rigid because rigidity meant stability. Even the street names are practical—no saints, no kings, just trades and functions.

Some people find Baixa cold. Too planned, too rational, lacking the soul of Alfama or the bohemian edge of Bairro Alto. I understand that. But I also understand what it took to build it. To lose everything and decide not to recreate the past but to invent something new.

Walking through Baixa, I kept thinking about the wooden cages hidden inside the walls. You can't see them. The buildings look like stone. But the flexibility is there, built in, waiting for the next shock. That feels like the district itself—solid on the surface, engineered for survival underneath.

Alfama is where Lisbon remembers. Baixa is where it moved forward

© PortugalExpert 2206

Castelo de São Jorge: The Old Heart on the Hill

The castle sits on top of everything. Literally. It's the highest point in central Lisbon, and from its walls, you can see the entire city spread below—the grid of Baixa, the maze of Alfama, the river cutting through it all.

I climbed up expecting a ruin. What I found was more complicated.

The Fortress That Changed Hands

The Moors built the castle in the 11th century. Not just as a fort, but as a citadel—the Alcáçova—where the governor and the elite lived. It was the last line of defense, the place you retreated to when everything else fell.

On October 25, 1147, it did fall. Afonso Henriques, Portugal's first king, took it after a four-month siege. He had help from Crusaders passing through on their way to the Holy Land. They stopped to conquer Lisbon first.

There's a legend about the final assault. A knight named Martim Moniz saw a side gate left open. He rushed it and wedged his body in the doorway so the Moors couldn't close it. He was crushed to death, but Christian soldiers poured through. The gate still exists on the northern wall. They named it after him.

I stood at that gate. It's small, unremarkable. You'd walk past it without noticing if you didn't know the story. But that's what happened—one man's body held it open long enough to change who controlled the city.

When the Heart Beat Strongest

For about 350 years, the castle was the center of power. Kings lived here. Guests were received here. In 1498, Vasco da Gama was welcomed back at the castle after finding the sea route to India. The place mattered.

The castle is dedicated to Saint George—the patron saint of England, not Portugal. That happened in 1387 when King João I married Philippa of Lancaster and gave her the castle as a wedding gift. It's an odd detail, but it stuck.

Then, in the early 1500s, the royal court left. King Manuel I built a new, luxurious palace down by the river where Praça do Comércio is now. The castle became obsolete overnight. It went from royal residence to military barracks, then a prison, then a storage depot for weapons. The heart stopped beating.

The Earthquake and the Fake Castle

The 1755 earthquake hit the castle hard, but it didn't destroy it. By that point, nobody cared enough to rebuild it properly. It sat there, damaged and ignored, for almost two centuries.

What you see today—the restored ramparts, the clean stonework, the romantic gardens—most of that is from the 1940s. The Salazar dictatorship wanted a national symbol, something to stir up patriotic feeling. So they reconstructed the castle. Not as it was, but as they imagined it should have been.

This bothered me at first. It felt dishonest. But the longer I stayed, the less it mattered. The reconstruction is part of the story now. The castle has always been whatever the current power wanted it to be—Moorish citadel, Christian stronghold, royal palace, prison, propaganda tool. The 1940s version is just another layer.

What You See

The walls are thick, weathered stone. Eleven towers still stand, including the Torre de Ulisses, which houses a Camera Obscura—an optical device that projects a real-time 360-degree view of the city onto a white dish inside a dark room. I watched the miniature version of Lisbon moving on the surface—tiny cars, boats on the river, people walking through squares. It felt like surveillance from another century.

The Torre do Tombo used to hold the kingdom's archives. Documents were literally tumbled into it for safekeeping. Now it's empty.

There's a gate in the inner courtyard called the Traitor's Gate. Small, easy to miss. It was designed for secret messengers or deserters—a way in or out that bypassed the main defenses. Every fortress needs an escape route.

The gardens inside the walls are unexpectedly green. Pine trees provide shade. Peacocks wander around screaming. They're loud, jarring, almost absurd. But they've been here for decades now, part of the reconstructed romanticism.

The View

I spent most of my time on the battlements. The view is why you climb up here.

To the south, the Tagus River. To the west, Baixa's perfect grid stretching toward the water. To the east, Alfama's tangled streets climbing down from the castle's base. North, the modern city sprawls out, indifferent to history.

From up here, you see how the city was built in layers. The Moors on the hill. The Christians rebuilding after conquest. The earthquake destroying the valley. Pombal imposing order. Each era stacked on top of the last, sometimes erasing what came before, sometimes preserving it by accident.

The castle is older than all of it. Or at least, the hill is. Archaeologists found remains from the Iron Age, then Roman, then Visigoth, then Moorish. Everyone who controlled Lisbon put something on this hill because the hill is the obvious place to be if you want to see everything and defend anything.

Why It Matters

The castle isn't Lisbon's heart anymore. That moved down to the river centuries ago, then spread out into neighborhoods the castle residents never imagined. But it's still the place you go to understand where the city started and why it started here.

Standing on the walls, I thought about the progression. The Moors built it to control the city. The Christians took it to claim the city. The kings abandoned it when they felt safe enough to live at sea level. The earthquake proved they were wrong. The dictators rebuilt it to remind people of a past that never quite existed.

None of it is pure. The history is layered, interrupted, reconstructed. But that's the point. The castle isn't a time capsule like Alfama or a fresh start like Baixa. It's a palimpsest—written on, erased, written on again.

When I left, I walked down through Alfama instead of taking the tram. The castle disappeared behind buildings almost immediately. From street level, you can't see it unless you look up deliberately. But it's always there, on top of the hill, watching the city it no longer rules.

The old heart still beats. Just slower now, and for different reasons.

Sé de Lisboa: The Fortress Cathedral Built on a Mosque

The cathedral doesn't look like a church. It looks like a castle that lost its moat.

Two thick towers flank the entrance, crenellated like battlements. The walls are massive, Romanesque, designed to take a hit. There's a rose window in the center, but it feels like an afterthought—a concession to faith in a building made for war.

The Sé de Lisboa was built in 1150, three years after Afonso Henriques took Lisbon from the Moors. They built it directly on top of the city's main mosque. Not next to it. On top of it. The message was clear.

The Site Beneath

In the Gothic cloister, there's an excavation pit. You can walk to the edge and look down into the layers of the city.

At the bottom, Roman street stones. Above that, remnants of shopfronts from when this was a commercial district under Roman rule. Then a medieval cistern. Then, crucially, an Islamic-era house and refuse dump—evidence of the people who lived here before the Christians arrived.

I stood at that pit for a while. It's not dramatic. Just broken stone, dirt, fragments. But it's proof that the cathedral didn't rise on empty ground. It rose on someone else's home, someone else's place of worship, someone else's daily life.

The Muslims who built the mosque didn't ask the Romans for permission either. And the Romans didn't ask whoever was here before them. Conquest works that way. You don't negotiate with the ground—you just build on it.

The Fortress Aesthetic

The cathedral was built during unstable times. The reconquest was fresh. The Christians held the city, but barely. The architecture reflects that anxiety.

Thick walls. Small windows. Towers that could serve as lookout points or defensive positions. The Sé wasn't just a place to pray—it was a place to retreat to if things went wrong.

That design saved it. When the 1755 earthquake hit, the cathedral survived. It was damaged, but it held. The fortress aesthetic turned out to be practical, not just symbolic.

Inside, the space is dark and heavy. Rib-vaulted ceilings, stone everywhere, an austere atmosphere that feels more like a crypt than a sanctuary. There's no lightness here, no soaring Gothic arches reaching toward heaven. This is faith anchored to the ground, fortified against collapse.

The Ravens and the Relics

The cathedral houses the relics of Saint Vincent, Lisbon's patron saint. His body was brought to the city in 1173 by boat, accompanied—according to legend—by two ravens who guarded the remains during the journey.

Those ravens became the symbol of the city. You see them on the coat of arms, on lampposts, on municipal buildings. They're everywhere now, detached from the story, just part of the visual language of Lisbon. But they started here, in this cathedral, tied to a saint's bones.

Inside the sacristy, there's a silver and mother-of-pearl casket holding Vincent's relics. I didn't see it—it's not always accessible. But knowing it's there changes the space. The cathedral isn't just a historical site. It's still functioning as a reliquary, still holding what it was built to protect.

Saint Anthony was baptized here too. Born in 1195 in a house a few steps away, he studied at the Sé and sang in its choir before leaving Portugal and becoming one of the most venerated saints in the Catholic world. There's a church built on his birthplace now, just down the hill.

Tram 28 and the Threshold

The famous yellow Tram 28 rattles past the cathedral's front entrance. The turn is tight—the tram screeches as it navigates the curve, close enough to the building that you could almost reach out and touch the stone from the window.

The tram connects the Sé to the rest of the city. It runs from Baixa up through Alfama, past the cathedral, toward the castle. The route is a timeline—you start in the 18th-century grid, pass through the medieval maze, and end at the Moorish fortress. The Sé sits right in the middle, the threshold between reconquest and reconstruction.

Standing in front of the cathedral, you can see both directions. Downhill, the orderly streets of Baixa. Uphill, the tangled alleys of Alfama. The cathedral belongs to neither. It's the hinge, the point where the city pivoted from one identity to another.

What Survival Means

The Sé has been damaged repeatedly. Earthquakes in 1347, 1755, and smaller tremors over the centuries. Each time, it was repaired. Not always faithfully—restoration in the 1930s tried to return it to a "medieval" appearance, which means some of what you see is as reconstructed as the Castelo.

But the core is real. The walls are original. The foundation is original. The placement—on top of the mosque, at the threshold of Alfama—is deliberate and unchanged.

What strikes me is the stubbornness of it. The building refused to fall. Not because it was beloved, but because it was built to last. It survived not through grace, but through mass.

That's different from Alfama, which survived by accident of geology. And different from Baixa, which was rebuilt by choice. The Sé survived because it was engineered to withstand attack, and that engineering turned out to be useful against earthquakes too.

The Conflict in the Stone

I keep coming back to the excavation pit in the cloister. The fact that they left it open, that you can see the layers, feels intentional. They could have filled it in. They didn't.

Maybe it's honesty. This is what conquest looks like—one civilization piled on top of another, the old life buried under the new foundation. The cathedral doesn't apologize for that. It just shows you the depth of it.

The Sé is where Lisbon stopped being a Muslim city and became a Christian one. That shift was violent. The siege lasted months. People died. And when it was over, the victors built a fortress-church on the most sacred site of the defeated.

You can condemn that or contextualize it or say it was the way of the time. But you can't ignore it. The building won't let you. It's too blunt, too heavy, too obviously built to dominate.

When I left, I walked downhill toward Baixa. The streets widened, the buildings lightened, the grid took over. The Sé disappeared behind me quickly, swallowed by the slope. But I kept thinking about the pit in the cloister, the layers of lives that got buried so the cathedral could rise.

History isn't clean. The Sé doesn't pretend it is. It just stands there, fortress-solid, built on top of what came before.